Free to Market for Thee But Not for Me

A closer look at the imbalance between provincial rent increases and inflation

By David Gargaro, editor RHB magazine, Oct/Nov 2021 issue

A rental property owner’s ability to increase rents typically depends on whether the province or territory has rent control. If there is rent control, the government sets the rent increase guideline, which is a percentage limit on the rent increase that can be charged absent special circumstances. If there is no rent control, the rental property owner can increase the rent by the amount they deem appropriate. In some cases, they’ll use inflation and increases in operating expenses to guide their decision-making on rent levels.

Average income levels and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) have increased over the last few years. However, rent increases in rent-controlled provinces have not kept pace. As a result, rental property owners are not charging market rates and are earning less than they should be.

Comparing rent increases to income and CPI

First, let’s look at how incomes have changed from 2016 to 2019 on a province-by-province basis. This is the most recently available data collected from Statistics Canada. Table 1 shows the average (and median) total income levels by province from 2016 to 2019.

Table 1: Provincial total incomes (average and median), 2016-2019

Over the four-year period, all but two provinces experienced increases in both their average and median incomes. The average income increased from 0.9 per cent to 10.5 per cent, while the median income increased from 2.2 per cent to 10.5 per cent. Therefore, the argument that most tenants cannot afford market-rate increases in rent is patently false, as their incomes generally increased over time. Holding the line on rent increases (i.e., freezing rents) is unnecessary and a burden on rental property owners.

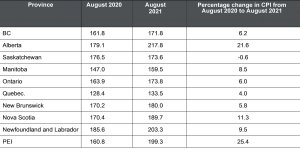

Table 2: Provincial CPI, water, fuel, and electricity, August 2020 and August 2021

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) measures the average change in prices over time that consumers pay for a basket of goods and services (e.g., transportation, electricity, medical care). Water, fuel, and electricity make up a significant portion of a rental property owner’s costs to operate their buildings, especially when tenants are not directly responsible for paying these expenses. Table 2 shows the provincial breakdown of CPI for water, fuel, and electricity, comparing August 2020 and 2021 (source: Statistics Canada).

Except for Saskatchewan, every province had a one-year increase in the CPI for water, fuel, and electricity, ranging from 4.0 to 25.4 per cent. These increases are much higher than the average rent increase for provinces with rent control. Rental property owners have not been able to recoup these increased operational costs through rent increases. As a result, their revenue fell behind their key operating costs during this period.

Note that Table 2 only shows the CPI for water, fuel, and electricity. It does not display increases in the costs of property maintenance and repairs, human resources, cleaning, and other expenses related to running a rental property. Considering that all of these costs (particularly cleaning) have increased, it is easy to see that revenues from rent have not kept up with expenses.

Province-by-province breakdown of rent increases

Let’s take a quick look at rent increases on a province-by-province basis for 2021.

British Columbia

British Columbia has rent control. However, the BC government has imposed a rent increase freeze until December 31, 2021. Rent increase notices cannot be sent to be effective between March 30, 2020 and January 1, 2022. If a rental property owner collects a rent increase within this period, the tenant can deduct the difference from future rent payments.

Effective January 1, 2022, the maximum allowable rent increase will be 1.5 per cent. Rental property owners must use a government-approved Notice of Rent Increase form to provide tenants with three months’ notice of a rent increase.

Alberta

Alberta does not have rent control, other than on the timing of rent increases. Rental property owners can only increase the rent if they have not increased the rent within the previous 12 months or since the beginning of the tenancy (whichever is later). The rental property owners must provide advance written notice. The amount of notice depends on the term of the tenancy. The rental property owner must give 12 full weeks’ notice for weekly tenancies, three full tenancy months for monthly tenancies, and 90 days for all other tenancies.

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan does not have rent control, other than on the timing of rent increases. Rental property owners cannot increase the rent during a fixed-term lease unless both the tenant and rental property owner agree to the amount of increase and the time of increase when the tenant signs the fixed lease. Also, the rental property owners cannot provide notice of a rent increase within six months of the start of tenancy or the date of the previous rent increase (whichever is later).

Manitoba

Manitoba has rent control. The rent increase guideline for 2021 was 1.6 per cent. However, the provincial government amended the Residential Tenancies Act to set a 0 per cent annual rent increase guideline for 2022 and 2023, to pass through reductions to the education property tax across rental housing.

The province sets the rent increase guideline annually, which takes effect on January 1. Rental property owners can apply for a larger increase in rent if they show that the guideline amount will not cover cost increases. Rental property owners can increase the rent once a year, and must provide tenants with written notice of the rent increase at least three months in advance.

Ontario

Ontario has rent control. The provincial government imposed a rent freeze for 2021, so rental property owners cannot increase rents above 2020 levels. The rent freeze ends on December 31, 2021, so rental property owners can provide tenants with 90 days’ notice before setting a rent increase at any appropriate time during 2022.

Effective January 1, 2022, the maximum allowable rent increase will be 1.2 per cent. Rental property owners may only increase the rent once every 12 months and must provide tenants with 90 days’ written notice. Rental property owners can apply to the Landlord and Tenant Board for approval to raise the rent by more than the rent increase guideline. They can also come to an agreement with tenants on rent increases in exchange for an additional service or facility (e.g., parking, air conditioning).

Quebec

In Quebec, there is no province-wide maximum on rent increases. Rental property owners can increase rent over the period of the lease for leases longer than 12 months. If the lease lasts less than 12 months, they cannot increase the rent during this period. When rental property owners give notice of rent increase, tenants can challenge the amount of the rent increase. Then the Regie Du Logement will apply percentage increases or decreases in relevant expenditures (e.g., electricity, gas, heating, maintenance and service costs) to calculate the allowable rent increase, which is often in the range of 1 to 2 per cent.

New Brunswick

New Brunswick does not have rent control. Rental property owners must provide tenants with advance written notice before increasing the rent. The amount of notice depends on the term of the tenancy. The rental property owner must give two full months’ notice for weekly or monthly tenancies and three full months’ notice for annual tenancies. If the tenant is on a fixed term tenancy, and the province has approved a rent increase during the year, then the rental property owners may increase the rent with three months’ notice. Otherwise, they must wait one year before increasing the rent.

Nova Scotia

Until the pandemic, Nova Scotia did not have rent control for most rental properties. The annual allowable rent increase for manufactured homes (i.e., mobile homes) and land-lease communities (i.e., mobile home parks) is 1.9 per cent for 2021 and 1.0 per cent for 2022. Rental property owners can only raise the rent once every 12 months. They must provide tenants with two months’ notice for weekly tenancies and four months’ written notice dating to the anniversary date of the tenancy for monthly and yearly leases.

However, on November 25, 2020, the provincial government imposed certain restrictions under the Emergency Measures Act, which will stay in place until the state of emergency is lifted or February 1, 2022. Under this mandate, rental property owners cannot increase the rent by more than 2 per cent per year, and cannot obtain an eviction order for renovations.

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador does not have rent control. Rental property owners can increase the rent by any desired amount, or can reduce the services or amenities provided at the same level of rent provided. The rental property owner must provide tenants with three months’ written notice of a rent increase. They may not increase rent during a fixed-term agreement, more than once within a 12-month period, or during the first 12 months of a weekly or monthly rental agreement.

Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island has rent control. The Island Regulatory and Appeals Commission sets the annual allowable percentage rent increase, which is 1.0 per cent for 2021 and 2022. Rental property owners must provide tenants with three months’ notice before the date of the rent increase. They can only increase the rent once per year or when a fixed-term lease expires.

Conclusion

Rental property owners consistently face challenges in running their businesses profitably. Average rent increases have not kept pace with the CPI, so rental revenues have fallen behind operational expenses. At the same time, average and median incomes have risen over time, providing most tenants with the ability to afford rent increases that keep pace with the market. While rental property owners in provinces without rent control can increase rents to keep pace with rising costs, the same cannot be said for rental property owners in the other provinces. It’s time to create an even playing field and let the market decide rents across the country.