UBCM Shenanigans

By Jens Von Bergmann and Nathan Lauster

The Federal, Provincial, and Municipal governance structure in Canada creates a fun pattern whereby all governments are happy to take credit for good things that happen, but when bad things happen, each tends to point the finger at the others. So we get the spider-Man meme.

When it comes to Canada’s housing crisis, pointing Spider-Men are all too common. But sometimes one level of government really is to blame. Recently the Province of BC and Federal government of Canada issued a joint Expert Panel report on the links between housing supply and affordability that placed a fair amount of blame directly on the door step of municipalities and their exclusionary land use controls. As housing researchers engaged in studying municipal zoning powers, we agreed with the expert panel, and provided them with our research pointing in the same direction (Summarized in Expert Report appendices 1, 2, & 3). After repeated difficulties moving provincially supported affordable housing projects through municipal approval processes, BC’s Minister of Housing (and Attorney General) David Eby has also indicated a willingness to go beyond pointing a finger at municipalities. He’s strongly suggested he’ll be offering legislation to reform and limit their powers to exclude housing, potentially following recent examples from New Zealand and California.

What did the Union of BC Municipalities offer by way of a response? Well, first they seemed to suggest there wasn’t a problem with supply at all. If there was a problem, it wasn’t their fault. Then they pretty much fell back on finger-pointing at every plausible villain for Canada’s housing crisis that wasn’t a municipality. In this, the recent UBCM Report titled Building BC: Housing Completions & Population Growth 2016-2021 demonstrates that BC municipalities are a) failing to recognize the role of supply in BC’s housing crisis, and b) failing to recognize their own responsibility for the crisis.

TL;DR

The report inadvertently makes a strong case for intervention from David Eby to curb municipal powers to exclude housing.

FAILING TO RECOGNIZE THE CRISIS

Let’s start with UBCM’s failure to recognize the problem. UBCM suggests that “housing supply […] has kept pace with population growth in British Columbia”, and erroneously concludes that this implies that housing is “not in short supply”. This posits the wrong relationship (ignoring how housing effectively sets a cap on population growth) at the wrong level of analysis (provincial as opposed to municipal/metro area) while ignoring the massive amount of counter-evidence (enormous price jumps, climbing rents, low inventories and rental vacancy rates, and administrative data documenting very few empty homes, homeless counts) as well as the basic but pretty robust theory of how supply and demand work together within a market context.

WRONG RELATIONSHIP

In short, overly simplified form: population growth does not equal the sum of demand. Population growth effectively represents only the portion of demand met by supply at current prices. And even there, population growth remains imperfect as a proxy, combining demographic processes with household formation set to mostly match housing.

In other words, housing effectively sets a cap on household growth. Household growth in turn sets a rough cap on population growth (Why? Because relatively few families double-up to share a single dwelling these days, in part because municipalities make it illegal to do so). We’ve covered this ground before many times and also in our appendix two to the expert report. All of this is before we even get to the well-known problems of how the Census a) undercounts people without any housing at all despite their best efforts, which include b) overcounting dwellings to reach out to anywhere people might possibly be staying.

Ultimately demand is a function of price. And if you think prices are too high, you can’t claim that supply meets demand. Just ask those people who have gotten priced out of the region; or those still here but doubling up, stuck in roommate situations; or living with parents for longer than they would like if they feel that their demand for housing has been met.

WRONG LEVEL OF ANALYSIS

The UBCM Report mostly provides analysis and figures at the provincial level, which is the wrong level of analysis when attempting to assess how housing markets are working. They provide one figure on “BC Major Census Metropolitan Areas.” CMAs more closely approximate housing markets, but weirdly Squamish and Prince George have also been added, despite neither being Major CMAs – or even CMAs at all. They’re too small to qualify as Metropolitan, so the Census categorizes them as Census Agglomerations. We’re going to return to this weirdness in a different post because the Squamish case in particular is pretty interesting and does not actually seem to support the narrative UBCM is pushing here. But for now we’ll just note that the inclusion of these Census Agglomerations in the figure is indicative of the lush Cherry Blossom season into which this report has been released. Why? Because this is cherry-picking.

IGNORING COUNTER-EVIDENCE

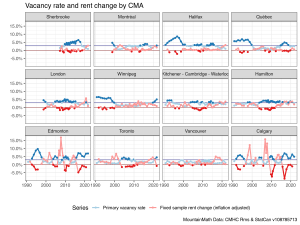

We have enormous counter-evidence of a housing shortage linked to the failure of supply to keep up with demand. This comes in the form of low inventories for sale and low rental vacancy rates which are robustly linked to price and rent increases. Here’s just the most recent data on the robust relationship between vacancy rate and rent change.

We also know that adding new units leads to vacancy chains that quickly open up other, older housing units across far corners of the housing market. See, for instance, these recent studies in Finland and the USA. Furthermore, we know that there are very few empty dwellings in high demand parts of BC based on results from BC’s very own Speculation and Vacancy Tax. The UBCM report doesn’t even attempt to take seriously all the counter-evidence to its attempts to claim that supply isn’t a problem in BC. Instead it quickly shuffles on to the next failure.

FAILING TO RECOGNIZE THEIR OWN ROLE

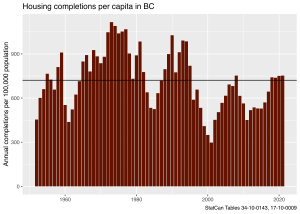

In addition to failing to recognize the crisis, the UBCM also fails to recognize their own role in making it. In particular, they argue that lots of new housing has been approved and constructed in recent years under municipal watch. The report looks at housing completions in British Columbia for the years 2000-2021, and notices that “more housing has been built in British Columbia over the past three years than in any three years in the past 20.” It is not clear what we are supposed to learn from this, there is no effort being made to relate this to the demand for housing nor to justify the time period selected.

Let’s choose one of many possible links to demand, normalizing new housing completions by population. After all, most new housing is occupied by local residents, who might be understood as steadily generating demand in accordance with population size. Let’s also extend our time scale back as far as accessible data will allow. How do recent completions per capita stack up?

Viewed this way the recent completions are barely above the long term mean. We can also see why 2000 might’ve been chosen by UBCM as a starting reference point. It’s when per capita completions hit at an all-time low across the province. Taking the longer view it looks like BC has been consistently under-building since the early 1990s, leaving behind quite a large hole in our housing supply.

Aside from cherry-picking in presentation and time period, there is also no effort in analysis to account for demolitions or CMHC methods changes (as occurred in 2013). Also once again, we’re looking at the province instead of municipalities. Housing just doesn’t work that way. If you are struggling to find housing in Metro Vancouver because that’s where jobs and opportunities are or maybe where you have strong connections with friends and family, it is entirely unreasonable to point to province wide housing stats and ask that you relocate to wherever housing may be available.

More directly to the point, as we noted in our appendix Three to the Expert Report, there is clear evidence that municipal zoning powers are both slowing and outright preventing the addition of new housing to municipalities. Municipalities play an enormous role in restraining housing. Exclusionary zoning is largely to blame for the hole in our municipal housing supply.

FINGER-POINTING

After downplaying the lack of housing as a cause of BC’s housing crisis and failing to recognize their own role in creating it, the UBCM continues, somewhat remarkably, to blame it on everyone else. If there is a lack of housing, it’s the fault of provincial regulations and the development industry itself. If there’s unaffordability in the province, it’s the fault of an even wider cast of villains, ranging from the federal government to investors big and small to pre-sale flipping to short-term rentals to the financialization of the economy as a whole. We attempted to address many of the alternative explanations for BC’s affordability crisis we expected to be identified in our appendix one to the Expert Report. But we must admit, UBCM came up with a few new ones.

We also have to admit that not all of the villains are implausible. For instance, it really is the case that the Federal and Provincial governments have dropped the ball on Social Housing investments. But when they’ve picked it up again in recent years, they’ve often found resistance to siting social housing coming from municipalities. Similarly, if municipalities want to blame big financial actors like REITs for affordability issues, they also need to recognize that such actors are very clear in where they invest: places “with constrained supply/demand attributes.”

Overall, it is certainly fair to note that housing is complex. Solving problems in one sector can create problems for others. At the same time, moving from housing scarcity to housing abundance is the first step to solving a lot of problems, and right now municipalities are all too often standing in the way. The UBCM report is evidence they probably won’t get out of the way in BC without a bit of stern nudging. That said, we should note as well that many municipal politicians also disagreed with the UBCM report. There are plenty of municipal politicians in BC who get it, even if the collective body purporting to speak for them does not.

UPSHOT

The above provides a summary review of the UBCM report. It’s bad. But maybe it’s bad enough to do some good in furthering the case for provincial restraint on municipal powers to exclude much needed housing.

This post barely starts to look at specific points and arguments brought up by UBCM within the report, many of which are misleading at best and display a shockingly amateurish level of analysis. Take the claim about “exponential” (do words still have meanings?) increases in pre-sale assignments, where the UBCM exploits the left-censored nature of their data source, and rising condo construction activity in Langley, and misinterpret this as a “remarkable growth in flipping of pre-sale condos.”

Another example is the shallow comparison of population to dwelling growth in Squamish. We have looked into this kind of argument in detail before when it was made about the City of Vancouver supposedly building more than enough housing, and how one particular ingredient of these claims, the number of housing units not occupied by usual residents, can easily be misinterpreted and has frequently been misinterpreted in the past in a number of different ways. For good measure it might be worthwhile to repeat this for Squamish, which showed the largest discrepancy between population and dwelling growth in the UBCM report, and we delegate that to a separate blog post.

In the meantime, the amateurish level of analysis on display by UBCM just underscores the problem. BC municipalities have been given enormous power over land use in the province. At the same time, they’re often under-resourced relative to the power they wield, so much so that they don’t recognize the damage they’re doing with their powers. This, of course, brings us back to Spider-Man: “With great power there must also come great responsibility.”

This blog was originally posted on Mountain Doodles and Home: Free Sociology!